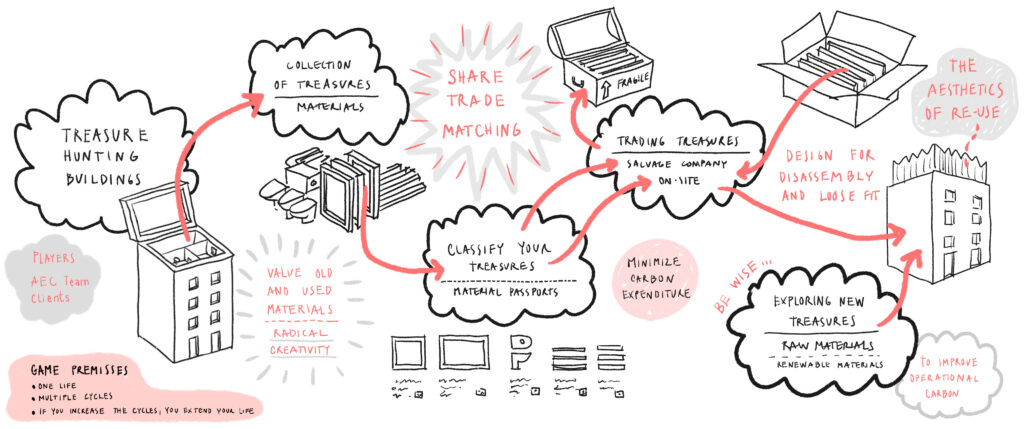

After four decades of working with existing buildings, our practice has witnessed firsthand the construction industry’s evolving relationship with material reuse. What was once standard practice – the careful salvage and redeployment of building materials – virtually disappeared in the post-war era, persisting only in the rarefied world of listed building conservation. Yet today, as the industry becomes increasingly comfortable measuring construction’s environmental impact, one truth has emerged with startling clarity: material reuse will be critical if we are to develop a built environment suitable for future generations without exceeding our planetary boundaries.

This isn’t merely about carbon accounting. The impacts of resource extraction on our natural environment, coupled with the mounting challenge of construction waste disposal, demand urgent attention. As the industry slowly shifts from ‘sustainability thinking’ towards ‘regenerative practices’, this material responsibility becomes even more prominent in our collective consciousness.

The irony is palpable. Propose material reuse in a contemporary design team meeting for a large commercial project and you’re often met with confused, blank faces. “Why on earth would a client pay more for reused materials when they could simply ‘recycle’ and purchase new?” The question reveals a fundamental misunderstanding of both economics and environmental impact – one our practice has been systematically challenging with considerable success.

Our recent work at 75 London Wall exemplifies this approach. We successfully reused 85,500 items (approximately 372t), whilst establishing and supporting innovative take-back schemes for metal ceiling tiles, ironmongery, and glass partitions. We’ve also championed high-grade aluminium and glass recycling programmes, creating closed-loop systems where materials maintain their construction-grade quality rather than being downcycled into general recycling streams unsuitable for building applications.

What have we learned? Unsurprisingly, robust processes must be established. Relationships with trusted suppliers require expansion, and room for innovation must be carved out. As architects, we must embrace flexibility – a willingness to listen to specialists, reach agreements with contractors, and protect our clients from both design and financial risks. The plan of action invariably changes as unexpected issues arise or concerns surface. We must remain nimble and fair to all parties whilst holding firmly to our conviction that reuse is entirely possible.

We’ve learned to accept that we’ll win some battles and lose others. Often, we learn most from projects that aren’t successful at implementing our reuse strategies – and that’s still something to be proud of. Every successful reuse story has several predecessors that taught us invaluable lessons.

Recently, our attention has turned specifically to stone. As a practice comfortable working with reclaimed stone in historic buildings, this expertise has begun spilling over all of our projects. We’re currently managing several schemes that are carefully removing parts of stone façades, reworking them, and reinstalling them with renewed purpose.

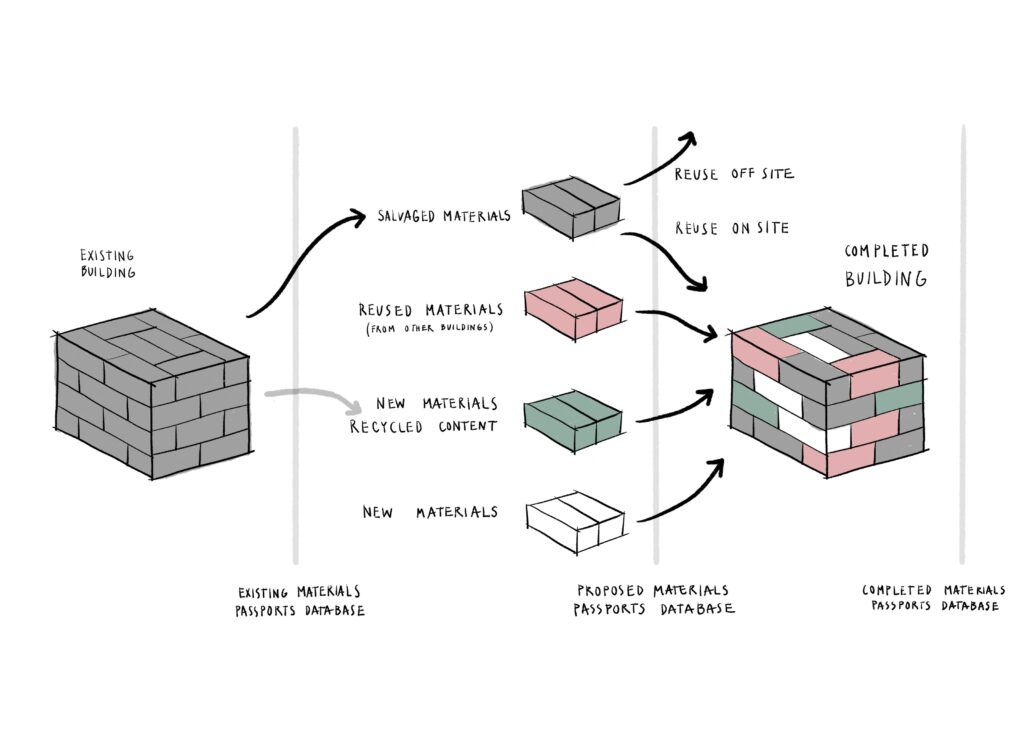

However, our current preoccupation is interior stone. The contradiction is stark: we specify new stone for virtually every building we design, yet we remove and recycle stone from nearly every building we refurbish. This raised an obvious question: what would a comprehensive reuse process actually look like?

Our stone journey began five years ago with a simple approach – we asked strip-out contractors to try salvaging interior stone. Several unsuccessful projects later, we discovered that standard adhesive systems and original specifications (typically too thin) usually resulted in breakages during removal. On the rare occasions we successfully extracted slabs, we struggled to find suitable homes for them, and they inevitably ended up in recycling bins regardless.

This year, our quest has intensified. We’ve cultivated numerous relationships within the industry, hoping some suppliers will recognise the benefit of taking back interior stone and beginning to stock reclaimed materials. We haven’t yet perfected the ideal specification for reuse, though industry consensus suggests a thickness between 20-30mm offers the best compromise. Discussions around optimal fixing details continue to evolve.

These conversations with stone specialists have been illuminating. The challenge isn’t merely logistical – it’s fundamentally technical. Current interior stone installation methods prioritise speed and cost over future recoverability. Thin-section stone bonded with strong adhesives creates an extraction nightmare. We’re essentially designing in obsolescence, in buildings that might reasonably expect a five or ten year ‘refresh’.

The solution requires rethinking specifications from installation onwards. Mechanical fixing systems, increased thickness tolerances, and accessible connection details all contribute to future recoverability. Yet these modifications often increase initial costs and complexity – a difficult conversation in value-engineering sessions.

Our practice remains committed to continuing this learning process, testing approaches until we succeed in establishing an interior stone reclamation process as natural as the stone itself. This requires patience, persistence, and partnership across the supply chain.

The stone industry possesses the technical expertise and craft knowledge essential for making reuse economically viable. What’s needed now is collective commitment to reimagining how we specify, install, and ultimately recover these beautiful materials. The circular economy isn’t an abstract concept – it’s a practical challenge requiring practical solutions.

After forty years of working with existing buildings, we know that the most sustainable building is often the one already standing. Extending this philosophy to individual materials – particularly stone, with its inherent durability and beauty – feels like a natural evolution. The question isn’t whether stone reuse is possible, but how quickly we can make it commonplace.

And on London Wall, of that 372t of strip out material reused, 62t is stone.